From Journalism to the Ivory Tower

How one Everyday Ambassador Navigates the Attention Economy

Change is hard. How do we break through deadlocks, overcome apathy, and foster better understanding? And how can media culture become a force for positive social change?

Meet Kaori Hayashi—a former journalist, a professor of media studies, and the Executive Vice President for Global and Diversity & Inclusion Affairs at the University of Tokyo.

Kaori has spent her career breaking boundaries—first as a foreign correspondent and now as a leader for gender justice in higher education.

At Japan’s top university, female students are so rare in some departments that classes must be organized to ensure no student is repeatedly the “only woman” in the room. Female professors make up only a small percentage of faculty. And when it comes to women in university leadership—well, Kaori is one of very few.

From making buildings accessible to persons with disabilities to allowing students to choose their own pronouns, Kaori is trying to make the university more welcoming. She faces significant resistance. But drawing from her experience in journalism and media studies, she has found ways to navigate roadblocks.

The Power of Stories: From Journalism to Gender Advocacy

Kaori recently shared her story in a conversation we had at Tokyo College:

“I began as a journalist, covering high-profile press conferences at the Bank of Japan, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and other major institutions—where, supposedly, the most ‘important’ news happened.”

But she quickly realized something:

“These so-called ‘big stories’ often followed predictable scripts. The same officials speaking. The same rehearsed statements.”

Care-Oriented Journalism: A New Perspective

Kaori found herself drawn to stories that weren’t being told—the voices left out of mainstream media. Women in rural communities. Mothers in city parks pushing strollers. Everyday citizens navigating struggles and triumphs that rarely made headlines.

Traditional journalism often devalues these narratives. It prioritizes a masculine ideology of journalism—where as she puts it, wars, conflicts, scandals, and politics dominate. These are the stories that drive profits and sustain journalism as a business.

Kaori began to explore what she calls care-oriented journalism—an approach that doesn’t just inform, but also serves to “support, empower, and nurture communities.”

“This doesn’t mean abandoning truth or facts. It means recognizing that journalism should consider the human impact of reporting. It should be sensitive to marginalized voices and amplify stories that foster social cohesion rather than deepen divisions.”

As she says, “In a world where media is often weaponized to divide and sensationalize, we need journalism that heals rather than harms, that connects rather than isolates.”

A Question That Sparked a Movement

Last year, Kaori and her colleagues launched a bold campaign at the University of Tokyo.

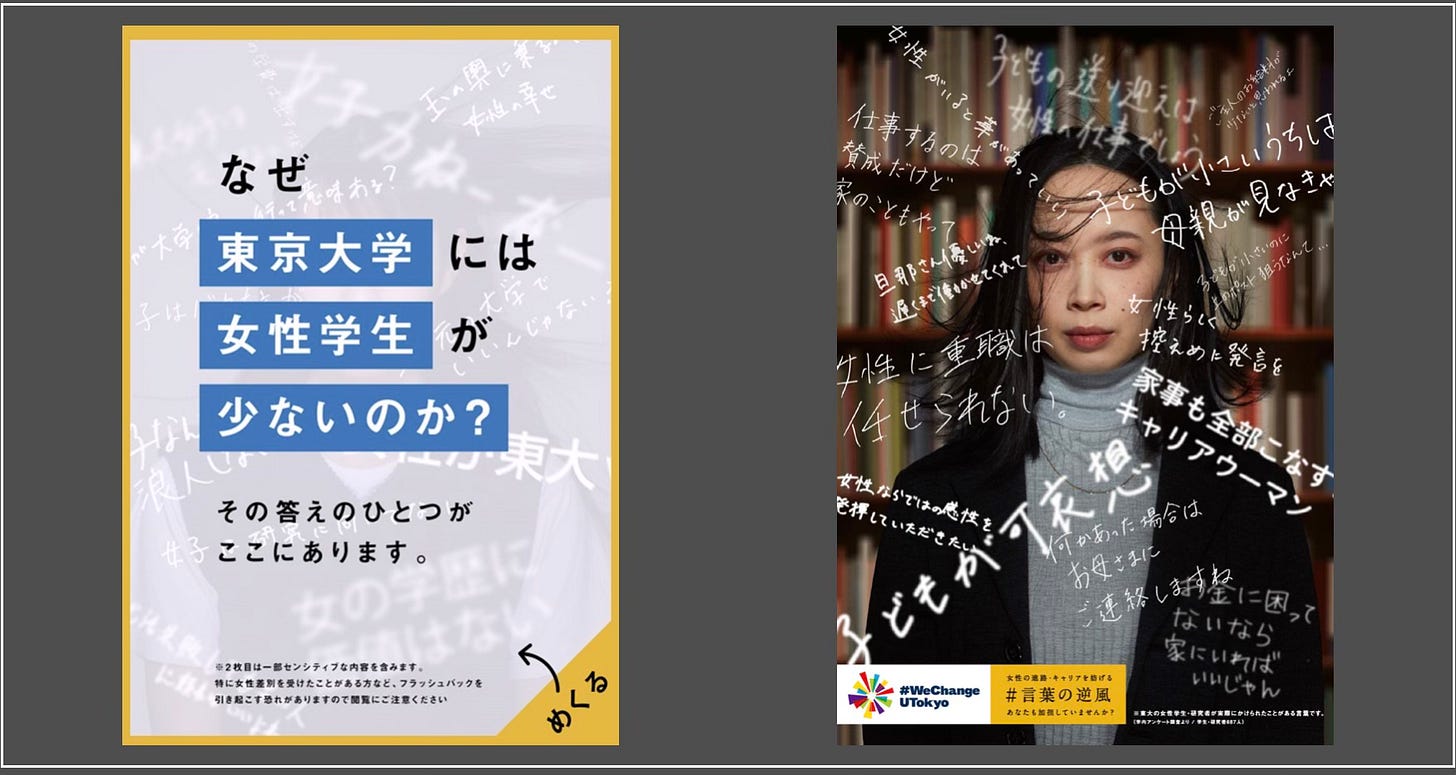

They put up posters with a large letter “Q”—for Question—asking:

“Why are there so few women at the University of Tokyo?”

(Image courtesy of Kaori Hayashi)

The posters were everywhere—even on cafeteria trays. The strategy, she says, was to create an environment in which “the question couldn’t be ignored.”

Reactions came swiftly. “Some welcomed the discussion. Others were uncomfortable. But most importantly, it started a conversation.”

Weeks later, she and her team followed up with a new set of posters—this time featuring answers they had uncovered through surveys:

(Image Courtesy of Kaori Hayashi)

“For example, many women at UTokyo experience microaggressions—subtle, often unintended comments or behaviors that discourage them from continuing in academia.”

The point of all this was to start a conversation: “Everyday conversations matter. Small, daily interactions can either empower or exclude people.”

Takeaways: Navigating the Attention Economy

In today’s attention economy, getting people interested is the biggest challenge.

If someone disagrees with you, you can debate them. But if someone doesn’t care, the conversation never even starts.

Kaori understands this—and uses the same “push” strategies that drive digital news to make people pay attention. Her cafeteria tray campaign took a technique used for clickbait headlines and repurposed it for social change.

“We don’t ‘read’ news anymore—we ‘check’ it,” Kaori notes. “Unlike a generation ago, when families gathered around the TV for the 7 o’clock news, today’s news is pushed to us in tiny, curated fragments, competing for our attention.”

Her campaign brilliantly pushed a critical question directly in front of every student and professor.

Kaori reminds us:

“If we want to build inclusive universities, workplaces, and societies, we must recognize that small, daily interactions can either empower or exclude people. Everyday conversations matter.”

This is what it means to be an Everyday Ambassador—turning ordinary moments into opportunities for connection and change.

Where Do We Find Hope?

Kaori’s work is exhausting. At times, it’s lonely. She constantly faces the question:

When do you confront institutions head-on, and when do you focus on long-term cultural change?

“Where do we find the hope to keep going?” she asks.

For me, I find hope in Kaori’s example—and in the lessons we can all learn from it.

Annelise, thank you for this insightful essay. The way Kaori challenges institutional silence with presence and persistence speaks to me. Visibility isn’t just about being seen—it’s about making the absence undeniable. The cafeteria tray campaign was brilliant in that way, turning a question into something that couldn’t be scrolled past or ignored.

I keep thinking about how much communication shapes reality. The way we speak, the stories we tell, and the silences we break can shift entire systems. This piece reinforces that for me.