I recently returned from the U7+Alliance of Global Universities summit, a gathering of university presidents from democracies worldwide, convened to discuss their collective input to the G7 process ahead of the upcoming Ottawa summit. The central questions on the table were prescient:

How can universities resist pressure from governments and protect academic freedom?

How can universities contribute to the fabric of our democracies?

How can universities provide leadership on issues from climate change to AI?

These questions are critical, and it's encouraging to see consensus emerging that universities should resist government pressure and defend academic freedom. But I believe we're still thinking too narrowly about what's at stake in this moment of cultural upheaval and about our true role and responsibility.

Beyond National Boundaries

The premise of Everyday Ambassador is that diplomacy isn't just for government officials—it's a responsibility for all of us, including universities and their leadership.

While universities remain largely localized, national institutions in both culture and funding structures (as we're painfully learning in the United States as the government takes aim at universities for political reasons), they are undeniably global actors. What universities do impacts the world, and what happens in the world impacts what universities do.

This reality means universities need a foreign policy, not just a free speech policy. They need allies, not just study abroad partners. This global perspective is essential for decision-making in our rapidly changing environment where local issues are increasingly globally driven.

I shared the following perspective with the assembled university presidents:

Our Diplomatic Heritage

Imagine this scenario: A brutal war erupts between erstwhile allies. Despite generations of shared culture, governments cease diplomatic contact, trade slows to a trickle, and borders harden.

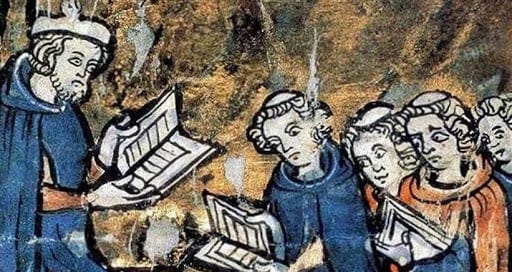

But then, a new river of discourse begins to flow—individuals in scholarly robes travel across hardened borders, appearing before crowds of students and scholars to share new wisdom, pass messages between governments, and advocate for peace.

This isn't some dystopian vision of our future. It's our actual past—specifically, the birth moment of universities in Early Modern Europe. During the Thirty Years' War, universities became principal sites of diplomacy through the movement of learned persons. These clerici vagrantes (wandering teachers) challenged siloed national views and helped rebuild shared European values.

This is our heritage and common identity. Universities' founding moment was one where princes were at war, and universities had no choice but to step into the role of diplomats.

The Moment to Step Forward

This is a period of dramatic change for the G7. Due to unilateral actions of certain governments, the G7 may be blocked from making significant progress at the Ottawa summit and could even be functionally imperiled in its current form.

Does this mean universities should retreat from multilateralism too? On the contrary—this is precisely when universities should lean into their heritage as global actors and invest in working together across national borders. In moments like these, multilateral engagement isn't optional but essential—for universities and for the world.

Universities’ Unique DNA as Global Actors

What distinguishes universities from other global institutions—governments, corporations, social movements? What is uniquely ours to do?

The answer is simple and clarifying: universities are guardians of the future. Our social function is to take the long view—to produce research that may only bear fruit in a generation, to educate the next generation of global leaders, and to care about issues of intergenerational justice that political and business cycles routinely undervalue: climate, culture, and peace.

This function naturally extends to universities' role in public diplomacy. As Joseph Nye noted when he coined the term "soft power," universities are prime examples. Or as former Secretary of State Colin Powell put it: "I can think of no more valuable asset to our country than the friendship of future world leaders who have been educated here."

But note that this "valuable asset" isn't realized immediately. It takes years for a young student to become a global leader. It's a long-term investment—and importantly, one that can't be immediately destroyed by short-term political actions. It's more durable than that.

The key point: while university presidents must pay attention to current events, they shouldn't be too beholden to them. Their focus should remain on their fundamental mission, the long-term.

Living Our Global Mission

How can universities embody their unique mission as global actors? How can university presidents serve as Everyday Ambassadors? It begins by leaning into universities' core competencies—education and research.

Example 1: The Erasmus Model

When you ask Europeans about their commitment to Europe and their Pan-European identity, invariably there's a story of time spent as a young person in another European country. That experience defines them, even when governments change.

That experience stems from one ambitious program in public diplomacy: the Erasmus program, established in 1987 to fund Europeans to study in other European countries. Students can even earn degrees by combining courses at different network universities.

While wonderful for individual students, for university leaders and policymakers, it's an investment in European identity. Through the program, people come to understand one another and appreciate their differences. Visionary European universities included the next generation of Europeans in the program from the beginning, incorporating former Soviet bloc states with the hope that this experience would prepare peoples and shift cultures.

This is more than public diplomacy—it's durable diplomacy. Something with greater force than a talking shop of heads of state—something that continues forward, even when government channels are blocked, for the sake of future generations.

Could we imagine an Erasmus among the universities of the G7 nations and other democracies? What a remarkable achievement that would be.

Source: https://ied.eu/blog/the-erasmus-plus-programme/

Example 2: Global Standards for Emerging Technologies

The statement university presidents delivered to the Canadian G7 Sherpa outlined universities' role in creating global standards for scientific and technological development.

We're in something of a Wild West moment for technologies like quantum computing and AI. Currently, coordination happens primarily through the market, with governments struggling to keep pace.

Universities as the genitors of these technologies should collectively claim leadership—serving as intermediaries between national and global financial interests, between governments and publics. No single university or nation's universities can do this alone. The only way to lead is to do so together, across borders.

A Call to Global Leadership

Although some university presidents understandably are pulling back and focusing on playing defense domestically, this is precisely the moment to play offense globally— it’s the moment for universities and their presidents to step into the role of Everyday Ambassadors. Because governments can’t do it alone, especially now.

University leaders can transform their deep personal and institutional connections into something greater—the engine of a collective diplomatic intervention in a world that desperately needs them. With their focus on the long-term, universities can help break the reactive news-cycle attention economy and refocus collective attention on imagining next futures.

It's up to universities to rise to the moment, to lean into a heritage of durable diplomacy in times of crisis that dates back to the early modern era.

In a world where traditional diplomatic channels face unprecedented challenges, universities may once again need to become the wandering teachers who keep the light of international cooperation alive.