I just returned from the United Nations Beijing Plus 30 conference—a gathering of the world's nations convened to assess progress on the commitments governments made toward gender equality 30 years ago at the Beijing Women's Conference. The question on the table was: is the world still committed to tackling gender inequality, from education and work opportunities for women, to nutrition, to access to health care, to sexual violence in armed conflict? And what's the role of organizations like the UN?

Thirty years ago, in Beijing,

the nations of the world committed to an ambitious plan of action to combat gender inequality. They promised to meet in thirty years to review their progress against those commitments.

I studied the meeting 30 years ago as a young academic and wrote a book about it, The Network Inside Out (Michigan Press, 2000). Beijing was a moment of hope and anticipation. Thousands of women came from all over the globe, all believing that the commitments made there would shape a better future for women everywhere. The conference saw legendary figures like Bella Abzug with her unforgettable hats, the ever-influential Betty Friedan, and celebrities like Sally Field. But the real stars were the women from every walk of life and every corner of the world—artists, professionals, wives of prime ministers, and revolutionaries—wearing t-shirts with slogans, energetically passing out flyers, holding up posters, all demanding change. The Beijing Women's Conference was also the meeting where Hillary Clinton gave her iconic "women's rights are human rights" speech.

As a researcher, I was following women from the Pacific Islands who had high hopes that a gender perspective would lead to decolonization, economic empowerment, and better healthcare for island women. They believed that the global movement for gender equality would be a driving force for change.

To be sure, the meeting was far from perfect. The activists from the Pacific fighting for decolonization struggled to have their issue seen as a "gender issue" at a meeting still largely led by first-world feminists.

Fast forward thirty years,

and the day had arrived to review those Beijing commitments.

So here we were at the UN. I attended as a delegate for the American Society of International Law.

I don't think anyone thirty years ago could have imagined how bad things would be for women globally thirty years on. Thirty years ago, even the Holy See, the state that is the Catholic Church, while it opposed abortion rights, stood firmly for women's education and empowerment initiatives that today would be denigrated as "woke." Today, the United States has, for the second time, rejected a female candidate for president, abortion rights have all but disappeared in some states, and universities are erasing mere references to gender from their websites. And the US wasn't even in attendance at the conference.

Today, cuts to US foreign aid are placing women, girls and sexual minorities in peril. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS reported that over 50% of HIV programs globally have lost funding or even been forced to close in recent weeks. A new WHO report warned that the same funding cuts threaten to upend progress made in the last twenty years towards a world in which women don't have to fear dying in childbirth. And the explosion of military conflicts around the world have contributed to backsliding on women's rights on just about every possible metric, from sexual violence, to education, to poverty.

The scene at the UN was strikingly different.

The number of attendees was tiny compared to Beijing, and the energy was muted. Gone were the passionate activists holding up posters or challenging government officials in the hallways and the streets. Instead, the observers' gallery was full of professional NGO types on their laptops, focused on their email.

In contrast to the fire of Beijing, governments were hesitant to call out the US. Instead of saying, "The US has cut funding for HIV/AIDS," we heard vague statements like, "Funding has disappeared."

Feminism has always been about naming what's wrong and demanding change. It's about imagining a different world and coming together across national and cultural divides to make it happen. Yet on the surface at least, that bold spirit seemed to have dissipated.

In my book The Network Inside Out, I already described how something was amiss in the celebration of global feminism that took place in Beijing. The focus often seemed to shift away from women and their struggles and towards an obsession of the UN itself, with its badges, bureaucratic processes, and negotiated documents. Maybe UN-style gender activism has just reached its endpoint, I thought, as I sat in the observer gallery.

And then,

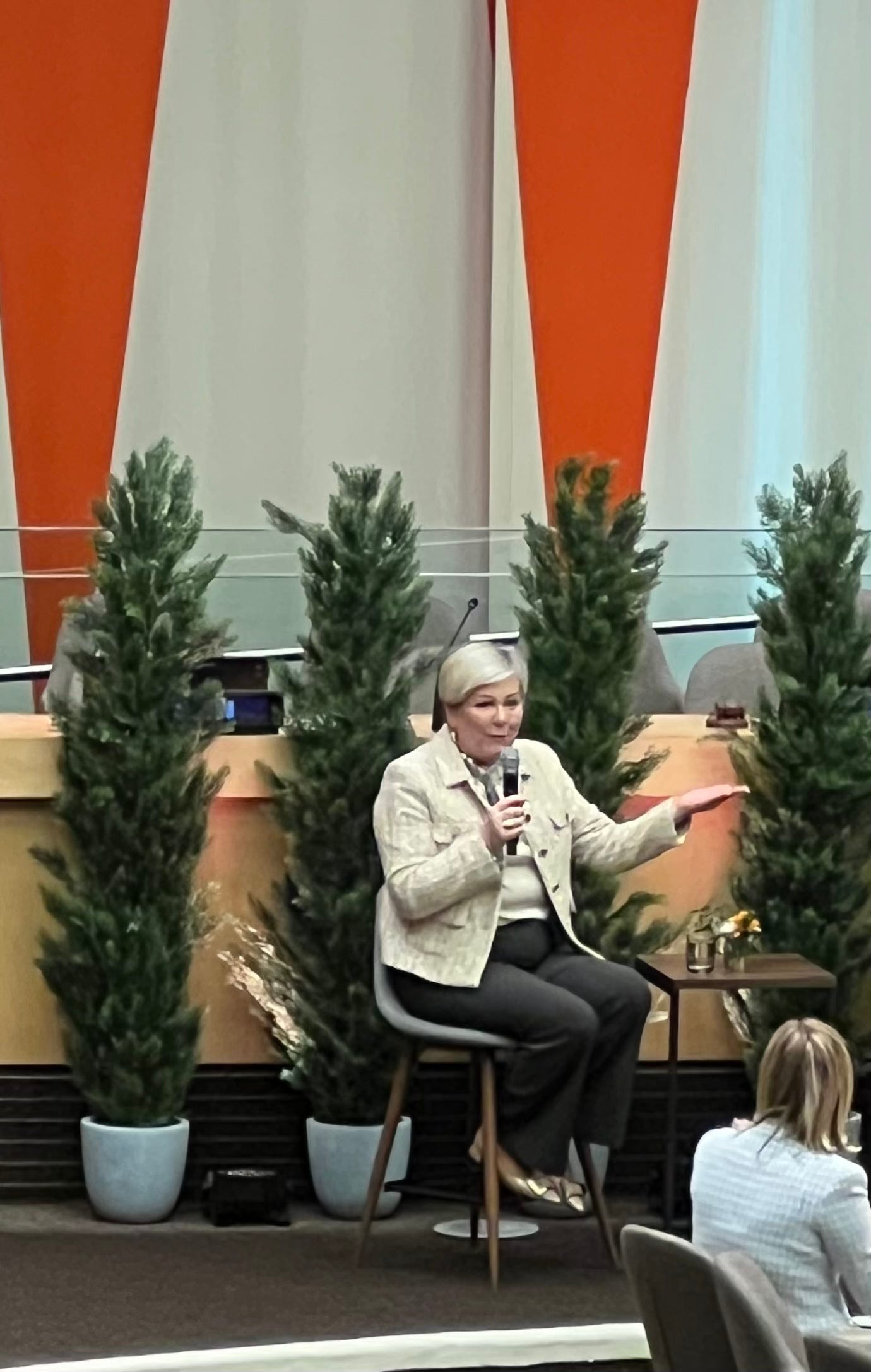

… at a town hall meeting of government and NGO participants, Halla Tómasdóttir, Iceland's second female president, called for a world-wide one-day strike by women to demand an end to masculine authoritarianism and advance women's equality.

She spoke from experience. Fifty years ago, the women of Iceland had done just that. For one day, nobody cooked, nobody took kids to school, nobody worked in shops or taught school or drove buses. She remembers being a small child, asking her mom, "Mommy, why aren't you cooking today?" Her mom responded, "Because I want to be seen." It worked. In just five years, Iceland had its first female president and today it has the world's first all-female government.

Tómasdóttir emphasized three virtues to defeat authoritarianism and bring about gender justice:

Courage—it comes from the heart, not the mind, she says.

Solidarity—because no one ever does anything alone.

Joy—because it's so much more powerful than fear.

Now we were talking!

Taking a page from Tómasdóttir, I started to notice all the issues that weren’t even named thirty years ago.

At the formal government meeting of diplomats, when it was time for a few representatives of civil society to speak, a trans woman from Brazil took the floor, with support from the government of Brazil. She spoke quietly, but passionately. "We won't hurt you. We are not your enemy. We just want to live with safety and dignity," she said. The NGO representatives in the gallery suddenly looked up from their email, and broke out into thunderous applause.

A Māori delegate named decolonization as the most critical gender issue in the Pacific—the very issue my research subjects had been unable to break through on thirty years prior. She denounced the New Zealand government, arguing that while it claimed to respect Māori culture, it remained silent about Indigenous genocide. A woman from the Middle East decried the lack of real regional consultation in creating the global agenda and insisted that for Arab women, decolonization is also issue number one.

A young woman representing the Girl Scouts spoke passionately about "online misogynist abuse enabled by tech giants" and how social media was destroying young girls' self-esteem and even leading to many suicides while the "broligarchy" made money.

Outside the formal deliberations, I stumbled into a meeting of feminist doctors from Nigeria. The energy was electric. They shared what they were doing about the issues in their communities, from health to sexual violence to discrimination against widows. The first world women in the room were now the apprentices—American college students from Lehigh University shared enthusiastically about how supporting the Medical Women's Association of Nigeria as interns had taught them so much and even changed their lives.

I attended more meetings of African feminists. At one meeting, a passionate debate broke out among participants about whether or not to support the rights of trans women. Someone denounced trans women as diluting the women's rights agenda. Someone else stood up to say that that is exactly what the enemies of gender equity want—ways to divide feminists and use divisions to bring everyone down. Another woman stood up to draw attention to the suffering of women in prisons. A poet read a joyful, sassy poem she had written for the occasion as participants laughed and voiced the lines of the refrain in unison.

So my report on Beijing Plus 30 is ultimately a hopeful one.

Global feminism is alive and well, but the center of gravity has shifted to the global south where women's health is under assault but where feminists are also declaring their independence from first world development institutions and charting their own path.

For the next two weeks on the podcast,

I'm excited to learn more about this shift. Today, I welcome Dr. Bilqis Alatishe-Muhammad. Bilqis is a physician, public health advocate, lawyer, researcher, and fierce champion for gender equity in Ilorin, Nigeria. She is also a leader of the Medical Women's Association of Nigeria. Bilqis shares what the fight for gender equity looks like in her world--and why the United Nations remains a critical partner in that work.

A Crisis Hidden in Plain Sight

Bilqis shares a startling statistic: 28.5% of all maternal deaths worldwide occur in Nigeria. To her, this is a critical issue of gender justice. “That’s why we keep making advocacy. Women are dying, and it can be prevented.”

Thoughts on the UN Conference

It was Bilqis’ first time at the UN. “It was amazing,” she recalls. “So many people doing so many things to give back, to change narratives, to improve health. You learn new things, you unlearn, and learn again.”

Despite skepticism in some parts of the world about the UN’s role, Bilqis remains a firm believer. “Women are the bearers, the carers. Without women, there is no world. So it’s important we keep having this conversation.”

So have a listen, and share your thoughts in the comments below: What do you think about the role of the United Nations in promoting gender equality, or social progress of any kind?

Next week, we'll travel to the other side of the continent, to talk with Austin Bryan, an anthropologist working with LGBTQ activists in Uganda.

Share this post